Trading Salmon for Kilowatts with Tucker Jones

By Teresa Gryder

Tucker Jones is the Ocean Salmon and Columbia River Program Manager for ODFW, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. He has a broad understanding and nuanced comments about what is happening with today's salmon restoration efforts. He spoke at a club potluck at Dan's house on 2/13/24 and we all learned a lot.

Tucker's passion is big river ecology. One influence he mentioned was a book called River of Memory; the Everlasting Columbia by William Layman. Multnomah County Library has 5 paper copies.

When Tucker talks about sturgeon his eyes light up; he finds their biology fascinating, whereas the situation with salmon is more interesting in its social and economic dimensions.

Our native white sturgeon are a valuable source of caviar. True caviar comes only from sturgeon. In the wild sturgeon take about 20 years to mature (meaning they have eggs/caviar) but when farmed (and fed continuously) they can reach 6 feet in length and reproductivity in as little as 7 years. Sturgeon can live as long as 150 years!

Once mature, sturgeon spawn every 2-5 years. In the wild sturgeon broadcast their eggs and sperm into the river, unlike salmon who build redds and guard that territory. Sturgeon prefer river environments with turbulence that keep their eggs and sperm mixed in the water column, instead of placid reservoirs where the eggs end up suffocated on the bottom. This is why they are usually found below waterfalls like Willamette Falls, and dams. He could have gone on about the sturgeon, but the talk was about salmon.

Tucker's language around the tradeoffs relating to salmon populations was direct: dams have by far the largest impact. We have "cheap power on the backs of salmon" and have "traded salmon for kilowatts". He says that if we want salmon populations in the Snake River we will have to remove those 4 dams, and if we don't remove those dams, we need to be honest about the cost.

Each dam "interaction" (where the fish must pass) results in about a 10% reduction in returning adults. (The actual reduction ranged 9-13% depending on the study). Multiple dams cause dramatic reductions in populations. He says he can reconcile himself to the loss of the Snake River salmon, but wants there to be a real conversation about the tradeoff.

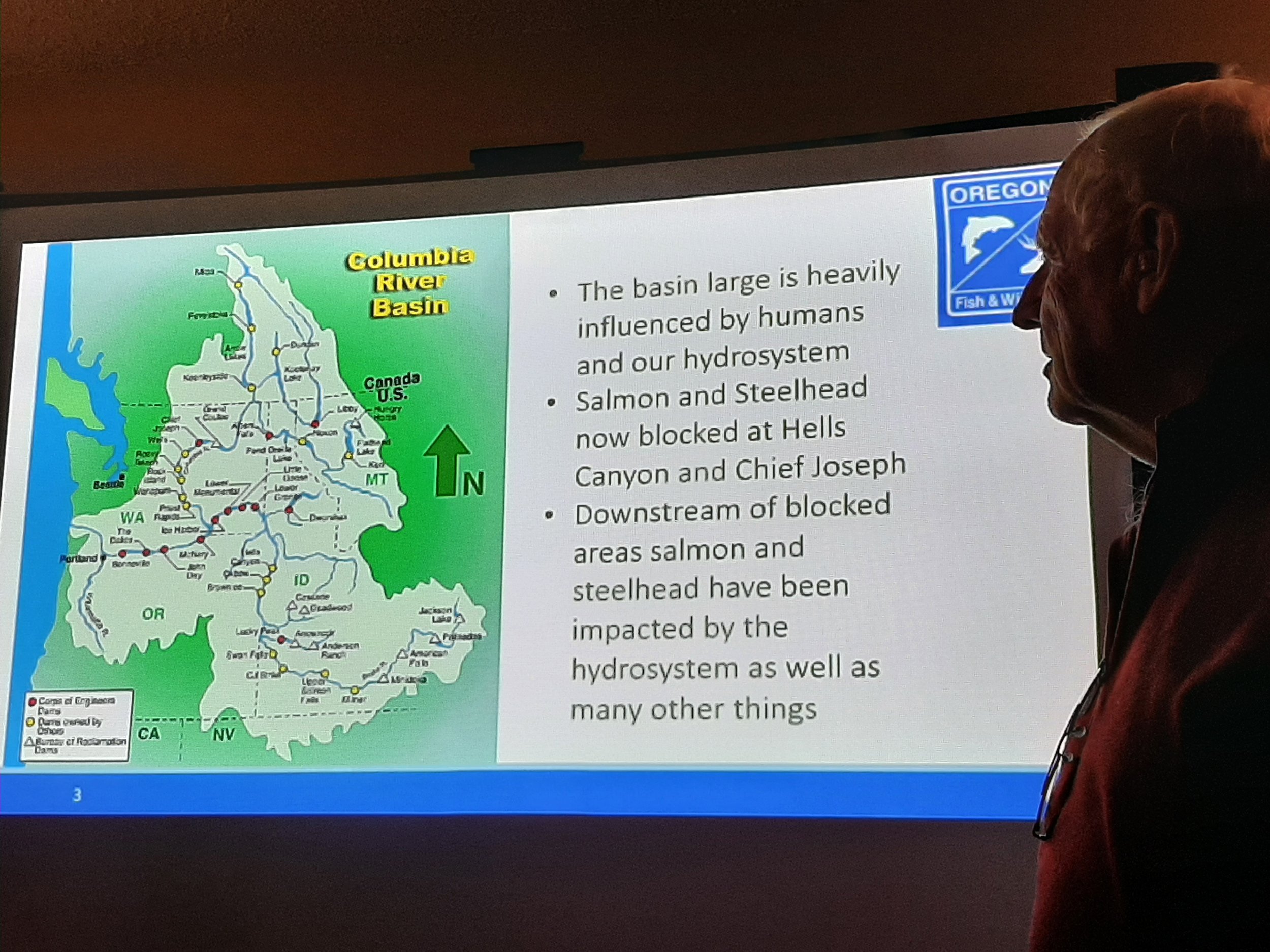

Chuck views Tucker’s slide about hydrosystem blockages for salmonids.

One tidbit that was new to me is the fact that young salmon do not swim downstream to get to the ocean. They instinctively position themselves heads upstream for feeding, and need a spring freshet (high water) to flush them to the sea. This is why reservoirs decimate migrating salmon--they don't know to go downstream, and they also are surface swimmers and the intakes for their downstream passage are often deeper than they normally go. Salmon infrastructure builders expected juvenile salmon to "sound down" (go deep) to go downstream, but this seems to have failed. This understanding makes me glad that the Klamath dam removals are happening all at once---if there are any juvenile salmon in that drainage, they are getting flushed to the sea along with all that muck from the bottoms of the reservoirs. We will see in a few years if they survive.

Barging juvenile salmon downstream has been happening since the 1990's. There are some who would deal with the downstream migration by increasing this effort, but it also appears to have failed. The metric used by the fish biologists is SAR which is a ratio of Smolts (baby salmon) to Adult Return. In short a 2 means that 2 adults make it back upstream when 100 smolts went downstream. The SAR needs to be at 2 or higher just to sustain existing populations, and for rebuilding populations they're looking for a SAR of 4-8. Records for the last 20 years show that most years the SARs for the Columbia are 2 or less---we're losing ground still, in spite of all our efforts.

You may recall the flooding that occurred in this region in 1996-1998. That flooding forced the dam managers to release water over spillways throughout the Columbia River system. Then in 2001 we had one of the best salmon returns seen in a long time. The downstream migration of salmon is facilitated by spilling water off the top, but past dam managers didn’t want to do this as they saw it as a "lost opportunity to generate power. Over time the region has come to recognize that spilling water is one of the best ways we have to support salmon recovery within the existing system." We just need to find ways to replace the lost power. Again, it's salmon vs kilowatts.

Another challenge salmon face in our area is the increased range of sea lions. Seals and sea lions are pinnipeds, and they both feed voraciously on salmon. Lewis and Clark named Phoca Rock, which is in the Columbia slightly upstream from the Angel's Rest trailhead, providing evidence that there were seals in the Columbia in 1805. Tucker knows of no evidence that sea lions had traveled so far upstream until more recently.

Wood installed in a Coweeman tributary.

Tucker had a surprising response to Will's inevitable question about the Coweeman. Will (our conservation chair) explained the situation and asked what we should do about wood installations supporting salmon spawning and rearing habitat. Tucker said that rather than attacking the lack of science behind these projects, we boaters should keep involved as allies in the fish enhancement project. If nobody knows or cares about the river, the fish are in trouble. By showing people our beautiful waters, we are indirectly supporting the movement to save salmon. In his view, our best role is as allies to the organizations intent on rebuilding salmon populations, and that those organizations should also recognize our value as a segment of the populace who actually care. By being involved longterm we might be able to influence the planners to include navigability and boater safety as important considerations in their engineering projects.

Raw salmon on cutting board, by Anne Stevenson.

For the salmon eaters among us, Tucker says Bristol Bay sockeye are sustainable and relatively inexpensive. "Columbia River chinook and coho salmon are also sustainable and local seasonal options but will be more expensive and are generally found in specialty markets and restaurants."

Salmon in grocery stores that is marked "Atlantic" has been farmed, most likely in BC. He says the species (Salmo salar) is from the Atlantic, that's why it's called that. He says salmon farming is "environmentally costly" and does not choose to support it with his food dollars, though he understands there may be reasons that others do.

There was a huge amount more communicated and I am disappointed that more people were not present for this program. If you were interested and just couldn't make it, you're in luck. Member Kathleen O'Malley is a salmon geneticist and has agreed to do a followup presentation about her research findings--and what she knows about salmon. Perhaps we should do it on zoom so that more people can attend without having to deal with city traffic.

Our deepest thanks go to Tucker for his fantastic presentation and his saintly patience with our barrage of questions. It's a good feeling to know that we have a guy like him managing Oregon's Ocean Salmon and Columbia River Program.

List of threatened and endangered salmonids in the Columbia Basin.